1. Beyond energy and emissions, what about the nature side – impacts on biodiversity, water, and land use. Can we understand more of this?

Environmental impacts of digital infrastructure extend well beyond carbon – Digital trade also has significant implications for biodiversity, water resources, and land use.

For instance, data centres frequently rely on evaporative cooling systems to regulate their temperature. These systems draw heavily on local water supplies, placing strain on water tables, particularly in regions already facing water scarcity or in proximity to densely populated areas. This pressure can exacerbate existing environmental and social tensions. Moreover, the physical footprint of digital infrastructure can have direct consequences for land use and biodiversity. While these developments may support low-carbon energy generation and digital connectivity, they can also lead to habitat loss, ecosystem disruption, and social dislocation. (E.g. in the Zeewolde, the Netherlands).

In addition, the growing problem of electronic waste (e-waste) represents a serious environmental hazard. Without adequate recycling and disposal systems—particularly in lower-income regions—hazardous substances from discarded digital equipment can leach into soil and water systems, further threatening both environmental and human health.

As the UK and other nations seek to position themselves as global digital hubs, it is essential to take a more holistic view of the environmental costs of digital infrastructure. This includes careful consideration of where such infrastructure is sited, how it interacts with local ecosystems and communities, and how its full environmental footprint—including water use, land impact, and waste—is managed.

2. There is a clear model for gathering and storing data, especially for training AI, but how would you create a business model for removing and deleting data? Are the incentives currently stacked against this?

This is an important first step. There is a significant volume of data that is simply stored without being used—referred to as “dark data”. The process of identifying and deleting unnecessary data is increasingly necessary. Initiatives such as, Digital Decarbonisation, (as well as some of the big tech companies), are exploring ways to improve the efficiency of AI algorithms and data processing.

However, we should be wary about framing this an individual choice to delete data, and ignoring the systemic issues business face. It is not simply a matter of individual choice – if it were easy and economically favourable, much of this data would have already been removed. Most organisations would, in fact, like to delete excess data—it represents a liability. But systemic and technical barriers remain significant. What is needed is a restructured system that supports and incentivises responsible data management at scale. Thus, there is also a key role for government intervention—particularly through regulation—to change the existing incentive structures. Without regulatory signals, the economics will continue to favour data accumulation rather than responsible deletion.

3. Can we ensure participatory decision-making around data decluttering (like deleting, moving, or archiving digital data), given its environmental and labour implications — especially when businesses control that process?

Decluttering is necessary. A significant share of stored data is never accessed—comparable to “piling newspapers you never read.” Unlike physical clutter, digital storage is largely invisible, leading to unchecked accumulation and wasted energy. As individuals, we store massive volumes of photos, files, and data, much of which is never used again. There is certainly critical data that needs to be retained—data that holds historical, organisational, or regulatory value, but organisations must develop clear data storage strategies that include structured deletion policies to avoid long-term inefficiencies and environmental costs.

However, there could be risks involved if there is not sufficient transparency or oversight. If businesses alone decide what data to delete or move, communities, workers, or regulators may not get a say — or even access to critical information. This raises questions of justice, accountability, and worker/community rights.

There could be a role for international frameworks to target this issue. There are precedents – for example, the Aarhus Convention ensures access to information, public participation, and access to justice in environmental matters, while the Escazú Agreement, includes provisions for environmental rights and participation — especially for vulnerable communities. These emphasise that people should be part of decisions that affect their environment and health — including digital-related waste and data practices. Could it be possible to apply participation through such treaties, not just to traditional environmental decisions, but also to digital processes like data management and tech waste? Such policy frameworks at an international level (and less so, at a domestic level) could play a role by creating legal requirements for corporate transparency, public oversight or participatory data governance, and involvement of workers, waste pickers and affected communities in discussions about digital practices.

International frameworks and policy could help in another way to support transparency, too. There is a significant additional challenge of how to standardise methodologies to account for embedded emissions in digital services and infrastructure. In the tech sector, there is enormous variation in what is measured and reported. Entire categories of environmental cost can be excluded depending on accounting approaches. Disaggregating digital supply chains is difficult, but essential if we are to understand and manage impacts.There is a strong case for developing consistent, transparent methodologies for monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV). Labelling and assessment schemes could also help drive better decision-making across the digital economy.

4. Why aren’t consumers being charged for the environmental costs of data storage? Would stronger price signals disincentivise excessive storage and energy use?

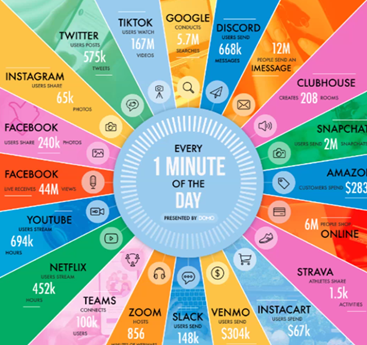

Consumers are rarely charged for the environmental costs of data storage — a systemic oversight that fuels excessive energy use and unsustainable digital practices. At present, data storage is effectively “free” or bundled into broader service offerings for many users, which contributes to digital hoarding and overconsumption. The infrastructure required to support this — from data centers to global server networks — is highly resource-intensive, drawing heavily on electricity, water, and land, and generating significant carbon emissions.

If environmental externalities were internalised into the cost of data storage, stronger price signals could help drive behavioural change. Users might become more selective about what they store, while businesses would be incentivised to build more energy-efficient models. Some proposals suggest a form of “digital carbon pricing” for data centres, which would reflect the true cost of digital services in environmental terms. Without these mechanisms, the environmental impacts of the digital economy remain largely invisible to end users and continue to scale unchecked.

However, the lack of pricing is not a simple market failure — it is a strategic feature of the digital economy. Data is not just a tool for current operations; it is a speculative asset. Its value lies in the possibility of future monetisation, especially through targeted advertising, predictive analytics, or training artificial intelligence systems. As such, companies treat data accumulation as an investment — storing everything in anticipation of later profitability. This is especially true in the age of generative AI, where large volumes of stored data are mined and monetised in training models, reinforcing the incentive to retain rather than delete.

Introducing environmental costs into this system is not just a technical fix — it challenges the underlying business model. Deleting data is not merely about saving energy; it risks undermining the entire speculative logic of digital capitalism. In this context, focusing solely on consumer behaviour change is insufficient. Structural change is needed: from regulatory interventions that mandate environmental accounting in digital services, to new norms and legal frameworks that constrain speculative data accumulation.

In short, while stronger environmental pricing could help moderate individual behaviour, real transformation requires addressing the economic structures that reward limitless data retention. The problem is not that storage is too cheap — it’s that waste is profitable.

5. Which countries are taking the lead in managing the environmental impacts of digital trade? What opportunities exist for international cooperation? How can trade policy encourage environmental accountability in digital sectors—particularly for AI?

The UK government has high ambitions in both the digital and environmental goods and services sectors, seeing them as essential for the strategy for UK growth.

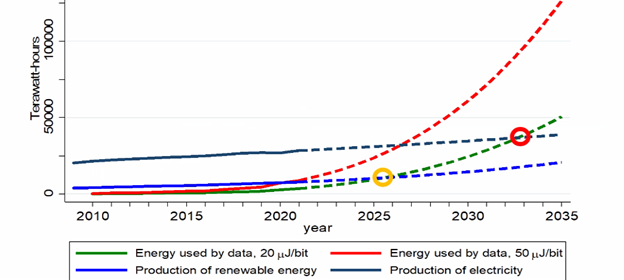

But, at present, few countries are taking a comprehensive approach. Even the UK government, considers perhaps only 10% of digital’s full environmental impact. The European Union, through the Green Deal and AI Act, has made more progress—particularly in aligning environmental standards with digital policy. But regulatory fragmentation is becoming a concern: the EU AI Act is setting new standards, while the UK currently relies on voluntary guidelines. The UK could lead by example, and introduce environmental performance requirements for AI products entering its market, but at a risk that such moves increase costs and further complicate compliance for international firms.

At its core, this remains a collective action problem. No one wants to move first, because doing so would raise costs and risk losing competitive advantage. Data centres are highly mobile and industries are price-sensitive. Without coordinated international regulation, meaningful progress will be difficult.