TaPP network held a rapid response discussion on 19th February 2025, to digest the implications of this new Trump Tariff era, including for the UK’s political and policy prospects for trading with the US and the rest of the world. Our speakers Nicolò Tamberi, Research Fellow in Economics at UK Trade Policy Observatory, Kathleen Claussen, Professor at George Town University Law Centre, and Gary Horlick, visiting lecturer at Yale Law School, spoke on their recent analysis about what Trump has done and plans to do, other countries’ reactions, and likely impacts on the UK.

Chapters

Share this article

TaPP Insight: Trump and Tariffs – Rapid Response Discussion

1. The terrifying economics of the Trump tariff regime

It’s been hard keeping up with the Trump administration’s trade policies. Since his second term began, ever-changing policy intentions and announcements – extreme in rhetoric and substance – have left businesses and international policymakers scrambling to a slew of tariff propositions, most significantly on Mexico, Canada, and China, as well as Europe.

The radical and uncertain nature of the past few weeks has made it difficult to assess policies’ long-term effects, but past experiences can offer some clues for economic models. They paint a bleak picture. Previous simulations of earlier tariff scenarios—assuming levies of 60% on Chinese imports and 20% on the rest of the world—suggested a sharp decline in U.S. economic welfare, with real income per capita falling by as much as $2,000 per year. Virtually all serious studies1 reach the same conclusion: tariffs are costly, and the US will bear a significant share of that burden.

A useful case study lies in Trump’s own record. The tariffs imposed in 2018 shared striking similarities with those now being proposed: last-minute announcements, selective targeting of specific countries and products, and an air of unpredictability. The response of US imports to those measures was stark – modelling shows that, in terms of the elasticity of imports to increase in tariff (% change in imports given a 1% change in tariff), a 10% increase in tariffs led to a 33% decline in aggregate imports over three years. The full response of production inputs to the imposition of a tariff is quick – drops were especially rapid for the agrifood sector and textiles and clothing sectors, for which a 1% tariff reduced imports by 5% or more within 6 months. But even in other sectors, the full response is felt in 18 months, and exhibits persistent reduced import levels, with up to 3.5%-4.5% drops in a sector’s2 imports per 1% tariff hike over 36 months later. These reactions are sobering, given that Trump’s tariffs on neighbours are set to be introduced at 25%, potentially halving imports from Canada and Mexico.

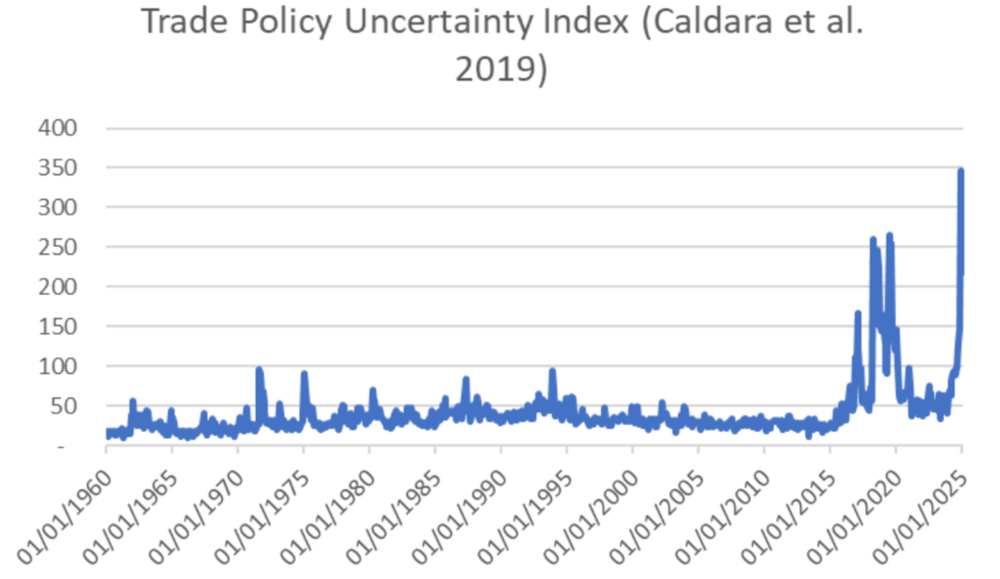

Beyond the tariffs themselves, the broader uncertainty surrounding U.S. trade policy exerts its own chilling effect. Trump’s erratic approach—announcing, pausing, and re-announcing tariffs—has sown deep unease among businesses. Caldara et al. (2020)’s monthly index of Trade Policy Uncertainty (TPU index) reached unprecedented levels beginning after the Trump’s first election in 2016 – reaching the level of 250 —well above the historical maximum of 100 of the past five decades. But now, only a few weeks into his second term, that figure has already surged to over 350.

Trade uncertainty has consequences. Nicolo Tamberi’s preliminary research on the NAFTA negotiation seems to offer a case in point. The mere prospect of withdrawal led to rising uncertainty from 2016 onward, which reduced US imports from Canada and Mexico.

Tariffs are not just taxes; they are signals. And the signal being sent by Trump’s new wave of protectionism is one of volatility. Businesses may brace for impact, but the ultimate casualty will be America’s own economic dynamism.

2. More chaos, more uncertainty

How can a government raise revenue while maintaining low taxes on the wealthy, in an economy with declining manufacturing and investment? Donald Trump seems to have chosen an answer – tariffs.

Trump’s return to tariff brinkmanship is now taking shape. So far, the only major new tariff formally implemented is a 10% duty on $400-500 billion worth of Chinese exports to the U.S. True, that his administration removed Chinese exports from the de minimis tariff exemption—waiving duties on goods valued below $800— but only to reinstate it days later when customs officials warned they could not handle the flood of parcels.

Yet, if we take Trump’s word, this is just the beginning. Steel and aluminium tariffs, of 25% and 10% respectively, are supposedly coming for (and arrived later) for every country. This defies conventional wisdom. Although 2018 tariffs on steel and aluminium of the same magnitude were a precursor, since then until now, thousands of product-specific exceptions were requested and granted for a product which could not be made in the US (no steel industry makes all type of steel products). These will be cancelled on 1 March. To “protect” an American steel workforce of only 85,000 (out of more than 150 million), American steel-using industries will now also justify tariffs on downstream steel products. But the evidence is not in favour of such a move: not only did steel industries see job-losses when hit by tariffs on steel inputs in 2018, but the tariffs introduced by Trump 2018 on and continued by Biden accompanied by increased prices from local producers, and apparently led to a 10 % decline in US consumption of steel and aluminium, presumably by moving steel-using production out of the US.

High and essentially indiscriminate tariffs are also coming for the US’s neighbours, Canada and Mexico. For the last 20 years, under NAFTA and then CUSMA, 99% of trade between Canada, Mexico and the US was tariff-free, allowing the ever closer industrial integration of the three countries. Under the new Trumpian regime of 25% tariffs on everything that meets USMCA origin rules from Canada and Mexico, all three economies would grind to a halt.

For the rest of the world – including Europe and other WTO members, the Trump administration plans to demand new tariffs on everything. Certain sectors face threats of targeted higher tariffs. In particular, Trump rails against Europe’s 10% tariff on American-made cars, compared to America’s current 2.5% tariff on most European cars – yet most US -produced “cars” are in fact SUVs, for which European manufacturers would face a 25% tariff when exporting to the US. Would Trump, in the name of “reciprocity,” lower duties on SUV imports to 10%? It seems unlikely.

What seems just as unlikely is the implementation of the declared intention to enact literally reciprocal tariffs – for each country (including individual European countries); i.e. charging a separate US tariff on the same item coming from different countries. These thousands of lines of new tariff policy would require constant updating, investigations (including murky questions of bound vs real tariffs), and are at best at odds with the priority of government efficiency and at worst, a totally unworkable and unrealisitc fantasy. This was so unmanageable that the Trump administration seem to be planning to announce April 2 country-specific tariffs at the same – fabricated – level for all products.

Meanwhile, Trump and his allies are actively undermining the analytical capacity of the U.S. government. Policymaking, which was already transactional during his first term, is set to become even more explicitly up for sale. The rule-based trading system is another casualty. The US, in practice, ceased acting as a proper WTO member during the Obama administration by disregarding certain tariff commitments and dispute rulings. Trump then took a sledgehammer to the WTO’s dispute settlement process, which was not reversed under Biden, but looks set to deteriorate further under Trump’s second term.

In summary, Trump’s latest tariff push follows a familiar pattern: protectionist rhetoric, unpredictable policymaking, and a disregard for economic consequences. These tariffs challenge other countries for countermeasures. For its part, China retaliated with tariffs added on $15 billion on US exports to China – however, this retaliation was done very carefully and selectively, on energy exports in particular. Most major exporters such as the EU say they will retaliate on equivalent amounts. If his first term taught the world anything, it is that trade wars have no winners—least of all the United States. Canada has already retaliated against a large amount of imports from the US with apparently more additions to the list. Interestingly, this has given a huge boost to the governing party, with a snap election called for April 28. Mexico has taken a more restrained approach to retaliation, as counties facing different factors choose different strategies as large tariffs to be announced by Trump on April 2.

The degree to which retaliatory tariffs might be effective in reversing the importing country’s new tariffs would seem to be based on 2 questions:

- The extent to which politically sensitive exporting industries in the ‘tariffing’ country depend on exports for their profitability/survival. This is not always easy to discern–some industries may export only 10 percent of production yet rely on those exports for its profits.

- Whether enough countries impose retaliatory tariffs on that product to reach that threshold. This would seem to require some degree of coordination by those countries, but the hard evidence for that is hard to see, without perhaps a perverse World Non-Trade Organization to coordinate.

3. The new dynamics of US trade policy

April 2nd is shaping up to become a pivotal day in Trump trade policy. This is the day just after the deadline for several key trade investigations—known by their three-digit statutory section numbers—to deliver their findings. These will deliver findings across all different agencies, including the Commerce Department and the USTR. Trump has already signalled his intent to impose tariffs following these investigations, although we do not yet know what the findings will be. But tariffs are not the only weapon in the president’s arsenal. Some of these statutes are open-ended in permitting the president to use still other measures to address the harms identified by the agencies in their investigations.

A second dynamic to watch in the trade policy of the coming months is the reaction of corporate America. Despite commentators’ strong warnings about the coming effects on the economy and the upheaval for business and profits, companies that might have been expected to speak out against it have remained quiet. Why? Corporations have better understanding and opportunity to make the case and get listened to by the administration than consumers (who may only vaguely be made aware of the effects of tariffs by seeing rising prices at the store), farmers (among the most vocal victims of Trump’s previous tariff actions, who have already expressed concern) or unions (whose support was ultimately not needed to get elected). One answer is that some corporations are nervous at making a public show of their opposition to these reforms. Instead, they may be hoping to use other, more discreet means. A flurry of lawsuits from import-dependent businesses should be expected if tariffs materialize. The legal avenues are narrow; most cases brought during Trump’s first term were decided in the government’s favor—but that may not deter companies that are facing extinction from challenging the new measures. Exemptions and exclusions will once again become the preferred battleground, with well-connected firms engaging in quiet lobbying in the hope of securing carve-outs, as they did in 2018.

Beyond the courts, the practical challenges of implementing Trump’s tariff agenda are immense. US Customs is already understaffed, and managing an increasingly complex tariff schedule will be a bureaucratic challenge, especially given ongoing government efficiency cuts.

There are many questions around trade deals too. Canada and Mexico have already given concessions to Trump in return for temporary tariff relief. But these unprecedented tariff schedules have been delayed, not avoided. Which other countries will be next? And more importantly, will any agreements prove reliable?

Congress, in theory, could step in. Lawmakers have the power to challenge Trump’s tariff policy because Congress has the constitutional prerogative to regulate commerce with foreign nations. On Capitol Hill, bipartisan frustration with Trump’s tariffs is growing, but not enough yet to lead to a coordinated response. Lawmakers might try to steer Trump’s trade ambitions in a different direction but there are many ways this could play out in Washington. The only certainty is that uncertainty over tariffs is likely to keep businesses, consumers, and policymakers on edge.

4. Discussion

In the discussion part of the workshop, questions were raised over how to address the tariffs, and different strategies taken by various countries, including the Global South, China, and the feasibility of a “Rest of the World” alliance, the future of the WTO, and financial markets, finishing with some points on what the UK should do.

1) How should we address Trump’s Trade turbulence?

When it comes to influencing Donald Trump’s trade policy, conventional lobbying strategies only go so far. Direct embarrassment—particularly through market reactions—has historically had the most impact. In addition, the stock market wobbled in response to tariff uncertainty, the administration took notice. Yet, as discussed earlier, corporate America remains strikingly absent from the current debate. Typically, when businesses feel the squeeze, they place a call to their senator, who in turn pressures the White House. But so far, Republican lawmakers have shown little inclination to push back, even on matters far closer to home—such as government shutdowns affecting public institutions3 or the dismissal of their own constituents from federal positions.4

One notable exception where business interests may carry weight is financial services. Both Elon Musk and Trump are deeply attuned to finance, making it a potential pressure point, particularly important for the UK. Unlike in manufacturing, where tariffs dominate, the trade battles in services play out differently—through regulation, market access, and diplomatic manoeuvring. The UK’s ability to secure favourable terms in this space may depend on whether it can leverage its financial clout effectively.

Indeed, different actors are deploying varying strategies to navigate Trump’s erratic trade policies. Some opt to keep their heads down, avoiding provocation. Others, like European leaders, have taken a more confrontational approach, signaling clear retaliation against American tariffs5. China, for its part, retaliates selectively, but reserves its real firepower for when it matters most6. Mexico and Canada, facing a full-scale assault on their trade agreements, pursued a multi-pronged response—retaliating with counter-tariffs, filing disputes at the WTO, and erecting non-tariff barriers.

For the UK and EU, reaction to American tariffs looks like a classic prisoner’s dilemma. While cooperation between Britain and the EU would be the optimal strategy, finding commonality to collaborate is unclear. What, if anything, can bring them together? The answer likely lies in shared interests—whether in financial services, supply chains, or the broader principle of defending a rules-based trading system. Without coordination, both risk being played against each other to secure piecemeal concessions from Washington.

Lastly, there may be a (slim) chance to rein Trump back internally. In 2017, Peter Navarro initially led the charge, with Robert Lighthizer later stepping in to exert control at USTR. Now, all eyes are on Jameson Greer, the new USTR. Lacking deep ties on Capitol Hill, his influence remains an open question. Can he rein in Navarro, now Trump’s Senior Counselor for Trade and Manufacturing, or will Trump’s most aggressive trade instincts continue unchecked? The coming weeks will reveal whether the administration’s trade agenda is steered by strategy—or by chaos.

2) How will the WTO fare? How precarious is its future?

he World Trade Organization (WTO) has long struggled with American indifference, and has not been able to look to the US for leadership in many years now. The US has refused to comply with key WTO obligations, disregarding bound tariffs and applying trade measures that openly discriminate between countries. While past US administrations saw some value in keeping the WTO as a negotiation forum, that no longer appears to be the case. Washington’s disengagement leaves the global trading system in a precarious position.

WTO members now face a difficult question: is there any point in continuing to use the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism? The organization’s ability to enforce rules has been crippled since the US dismantled the Appellate Body7, effectively rendering it impossible to resolve trade disputes. Yet, some countries still see value in maintaining the system, even if only to preserve what remains of global trade governance. The question is whether enough members can push forward without U.S. support—perhaps even by creating parallel mechanisms that sidestep American obstruction.

There is at least one reassuring sign: the US ambassador to the WTO, María Pagán, is a seasoned trade expert who understands the stakes involved. That offers some hope that America will not seek to fully dismantle the institution. But will the US go so far as to withdraw from the WTO entirely? While such a move remains unlikely, it cannot be ruled out under a second Trump administration.

In reality, the best-case scenario may simply be one in which the WTO survives without further disruption. The organization has already been weakened by years of US neglect, and there is little chance of Washington resuming a leadership role in global trade. For now, the world’s trading partners must navigate an environment where the rules exist—but enforcement remains an open question.

3) Can the Rest of the World unite on trade? Is an “Alliance of the Rest” plausible?

The idea of an “Alliance of the Rest” to counterbalance US trade policies and preserve the global trading system going sounds appealing. And in theory, it is possible. The US accounts for around 13% of global GDP, a significant share but far from overwhelming. A coordinated effort by Europe, Japan, Canada, and emerging economies could, in principle, sustain the rules-based trading order without American leadership.

Yet in practice, such an alliance appears unlikely. The EU, the natural next leader, is still grappling with how to respond to US tariff uncertainty. For now, the idea of a new trade alliance remains more of a thought experiment than a realistic prospect. While international coordination may emerge in specific areas, a fully-fledged “Alliance of the Rest” seems improbable. The world may still rely, however reluctantly, on a U.S.-dominated system—whether rules-based or otherwise.

4) Is the Global South in the Firing Line?

For developing economies, the shifting tides of global trade policy present both risks and opportunities. While much of the focus is on how America’s tariffs impact major economies like the EU and China, the Global South is not immune to collateral damage. Many developing countries rely heavily on trade preferences, open markets, and stable global supply chains—precisely the elements that US trade policy is now disrupting. For commodity exporters, new trade barriers can reduce demand for raw materials. For manufacturing hubs integrated into global supply chains, increased costs and uncertainty may lead multinational firms to reassess their sourcing strategies. The IMF and World Bank—institutions originally designed to provide stability and support to the developing world—will be needing to rethink their role in light of this volatility.

That said, some Global South countries may find ways to benefit from the fractures in global trade—particularly if Western firms seek alternative suppliers to bypass tariffs on China. Others may use the moment to push for a stronger voice in international economic institutions. But for most, the new trade order presents more threats than opportunities. If Washington continues to upend global rules, developing economies may find themselves caught in the crossfire, with little say in how the battle plays out.

5) China’s Calculated Response

Thus far, Beijing’s reaction to the latest round of US tariff announcements has been measured, even restrained. But China’s real response began long before the latest announcements. The government has been quietly adjusting its policies, including the withdrawal of certain export subsidies, in anticipation of mounting trade barriers. Rather than leaning into retaliation, Beijing appears the steering its firms away from overreliance on exports. A 10% tariff on Chinese goods is undoubtedly painful, hitting manufacturers and jobs in already fragile sectors. China’s AI and tech sectors will particularly struggle.

The question remains: how will China position itself in the evolving global order? Could it take a more assertive leadership role in regional trade groupings? So far, its focus has been on strengthening ties within Asia, particularly through mechanisms like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Hidden at the heart of this issue is investment unfairness. While Western governments decry China’s industrial policies, the reality is that different sectors generate profits in different ways across various countries. Beneath the surface, a game of smoke and mirrors is unfolding—one in which investment screening may prove just as decisive as tariffs themselves.

6) Financial markets versus reality

A puzzle for commentators is that Wall Street seems unfazed. The S&P 500 continues to climb to historic highs, seemingly brushing off the looming threat of sweeping tariffs. Do investors know something the rest of the world doesn’t? Or they are dangerously underestimating the economic consequences of Trump’s trade agenda?

So far, markets appear to be pricing in a ‘manageable’ scenario—perhaps assuming that some tariffs will be watered down, delayed, or subject to carve-outs. But if Trump follows through with a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico, the economic impact would be catastrophic for all three economies. Supply chains deeply integrated over decades would face severe disruption, and inflationary pressures would surge. Markets may not be worried now, but the moment businesses start feeling the real effects, confidence could erode quickly.

7) Reflections and Advice for the UK Government

So much has been announced in terms of the Trump administration’s intention for tariffs. But very little is yet in place. Could this just be the knowingly challenging yet unrealistic opening gambit to begin negotiations to come? If so, the UK should make the most of such negotiating chances.

In world of so many uncertainties for these upcoming tariffs, the UK should prioritise cooperation with others, because that will be the main – if not the only – possible avenue for leverage. In an ideal world, the UK, the EU, China and the rest of the world’s largest economies would cooperate, and the US would have no choice but to go along. The UK could be deeply involved, leveraging its position in CPTPP and other agreements to cooperate with the EU. But this kind of “Alliance of the Rest” as discussed above, is unlikely to happen for years to come, given the deepset reluctance to give up the US as the leader of the global trading order.

Nevertheless, the UK is in a very different position to the EU. (Smaller and more agile, Japan serves as a more useful comparator than the EU.) The UK has a special position, as it speaks the language and has a close relationship with the US beyond trade. It also does not lack significant defence spending – a key Trump administration criticism of the EU. This may place the UK in a unique position to broker key negotiations between the EU and US, and keeping negotiations open is essential. Low hanging fruit could include economic security agreements. Friendships can continue in less traditional areas – already identified by HMA to the US Peter Mandelson as IT and digital trade8 – to maintain channels of communication with the Whitehouse, the hill, and congressmembers.

References and Recommendations

Aaronson (2025) CIGI: Susan Ariel Aaronson, “US Import Tariffs Will Hurt Americans, Too”, 12 February, 2025. https://www.cigionline.org/articles/us-import-tariffs-will-hurt-americans-too/

Amiti et al (2019) Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. 2019. “The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4): 187–210. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Fjep.33.4.187&ref=aussienomics.com

Caldara, Dario, Matteo Iacoviello, Patrick Molligo, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea Raffo (2020), “The Economic Effects of Trade Policy Uncertainty,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 109, pp.38-59.

Caldara, Dario, Matteo Iacoviello, Patrick Molligo, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea Raffo, (2019) “Does Trade Policy Uncertainty Affect Global Economic Activity?,” September 4 2019.

Clausing and Lovely (2024) PIIE: Kimberly Clausing, Mary Lovely “Trump’s bigger tariff proposals would cost the typical American household over $2,600 a year”, 21 August 2024. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2024/trumps-bigger-tariff-proposals-would-cost-typical-american-household-over

Fajgelbaum et al. (2020) Pablo D Fajgelbaum, Pinelopi K Goldberg, Patrick J Kennedy, Amit K Khandelwal, The Return to Protectionism, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 135, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 1–55, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz036 https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/135/1/1/5626442

Gasiorek (2025), UKTPO: Michael Gasiorek, “How much damage could Trump’s tariffs do and what can be done?” 3 February 2025 https://www.uktpo.org/2025/02/03/how-much-damage-could-trumps-tariffs-do/

Gasiorek, Sen (2025) UKTPO: Michael Gasiorek and Anupama Sen: “Trump’s tariffs: How much should we be concerned and why?” 24 January 2025 https://www.uktpo.org/2025/01/24/trumps-tariffs-how-much-should-we-be-concerned/

Henry (2025): UKTPO: Ian Henry, “Will Trump’s tariff policy correct an unusual imbalance?” 10 February 2025. https://www.uktpo.org/2025/02/10/trump-tariff-policy-correct-imbalance/

Paulsen (2025) LSE: Mona Paulsen, “How the US’ trading partners should respond to Trump’s coercive strategy of ‘tariffication’”, 4 February 2025. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2025/02/04/how-the-us-trading-partners-should-respond-to-trumps-coercive-strategy-of-tariffication/

Tamberi (2024a): CITP, Nicolo Tamberi: “Trump’s tariff proposal could cost over $2,000 (£1,500) per capita to US consumers”, 16 October 2024. https://citp.ac.uk/publications/trumps-tariff-proposal-could-cost-over-2000-1500-per-capita-to-us-consumers

Tamberi (2024b): CITP, Nicolo Tamberi: “Will Trump impose his tariffs? They could reduce the UK’s exports by £22 billion”, 8 November 2024, https://citp.ac.uk/publications/trumps-tariffs-could-reduce-uk-exports-by-22-billion

-

See Clausing and Lovely (2024), Fajgelbaum et al. (2020) and Amiti et al (2019). (back to content)

-

In this case, chemicals and plastics. (back to content)

-

E.g. the JFK memorial library – See more here. (back to content)

-

See more here. (back to content)

-

See more here. (back to content)

-

See more here. (back to content)

-

See more here. (back to content)

-

See more here. (back to content)